I have been thinking a lot about matrix multiplication recently. Specifically, if you’re multiplying two matrices of size \(n\times n\), I find it very hard to understand how it’s possible to achieve this in better than \(O(n^3)\) time. The reasoning here is that you have to calculate \(n\times n\) elements of the output and for each element you have to do \(n\) calculations, leading to \(O(n^3)\) calculations.

In spite of this I am aware that there are algorithms that can multiply the two matrices in significantly less time, in fact the current best algorithms can do so in \(O(n^{2.3727})\), a huge amount better than \(O(n^3)\). I spent a little time looking into this, and found that the history of matrix multiplication is surprisingly interesting.

It turns out that in computer science circles this scaling is so important that is has its own symbol, \(\omega\). The quantity \(\omega\) is defined so that the scaling of any given algorithm is \(O(n^\omega)\). Concretely, the naive idea I put forward in the first paragraph has \(\omega=3\). How did we get from the naive algorithm to today’s \(\omega=2.3727\)?

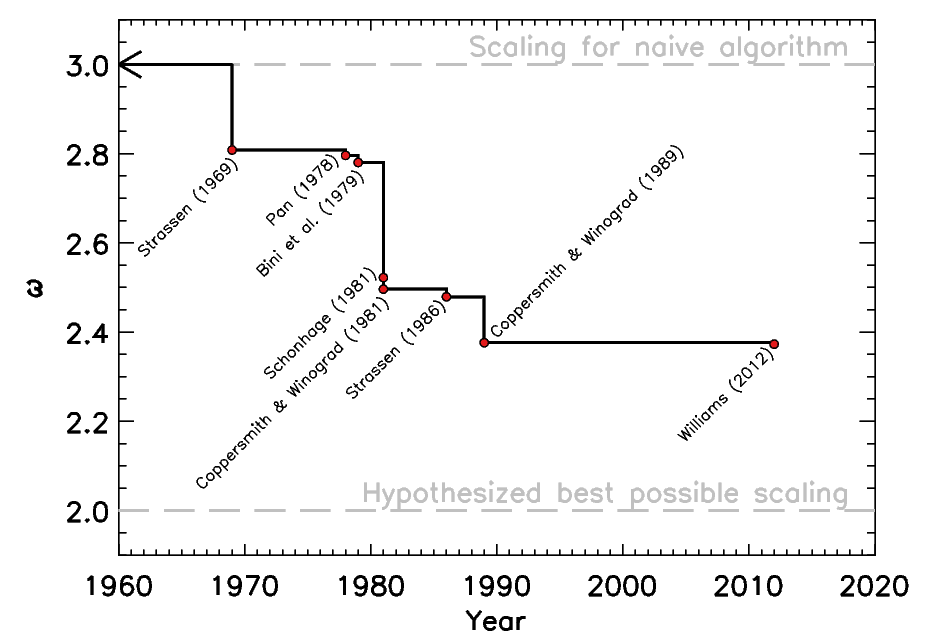

The answer is that we got there in fits and starts. In the following graph I have collected some references showing how the best known value of \(\omega\) has changed with time. Here is a graph showing the best known value for \(\omega\) over the years.

This graph shows the best currently known value of \(\omega\) as a function of time. The upper, horizontal bar shows the scaling of the \(O(n^3)\) algorithm, and the lower, horizontal bar shows the hypothesized (although not yet realized) best possible scaling for a matrix multiplication algorithm, which is \(O(n^2)\).

Since time immemorial people have known the \(n^3\) algorithm (or just assumed that no improvement is possible). Absolutely no progress was made in this direction until 1969, when Volker Strassen published his paper demonstrating an algorithm with \(\omega=2.808\).

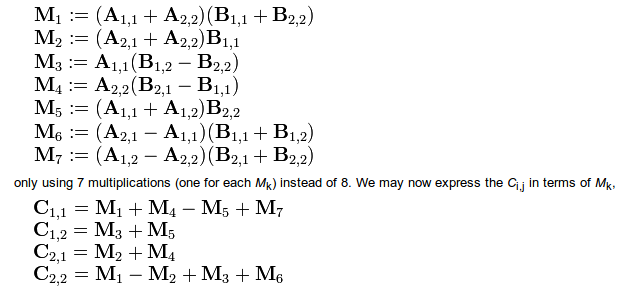

I find the Strassen algorithm unbelievable (I guess the polite scientific term for that is ‘highly non-trivial’). In short, Strassen found a way of reducing the number of multiplications you need to do to multiply two \(2\times2\) matrices, \(A.B=C\), from 8 to 7, via a really convoluted series of equations

Sometimes I look at algorithms and think to myself “yes, I could have thought of that”. This time, though, I just have no idea where it came from. There was a leap of insight taken somewhere along the line there that I just can’t begin to fathom. Really incredible stuff.